Is there space for another picture on your wall? If so, the Department of Homeland Security has a recommendation. Veering briefly from its mission of protecting Americans against terrorism, DHS has posted an image that offers a fascinating glimpse into the way our current ruling group views America and its history.

Cabinet offices do not normally endorse works of art. Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem and her team have become the exception. They recently posted the evocative 1872 painting “American Progress” with a patriotic caption: “A Heritage to be proud of, a Homeland worth Defending.”

When “American Progress” was painted, the United States was on the brink of huge transformations. President Trump and those around him like to imagine that the same is happening today — the dawning of a new era of peace and abundance under their guidance.

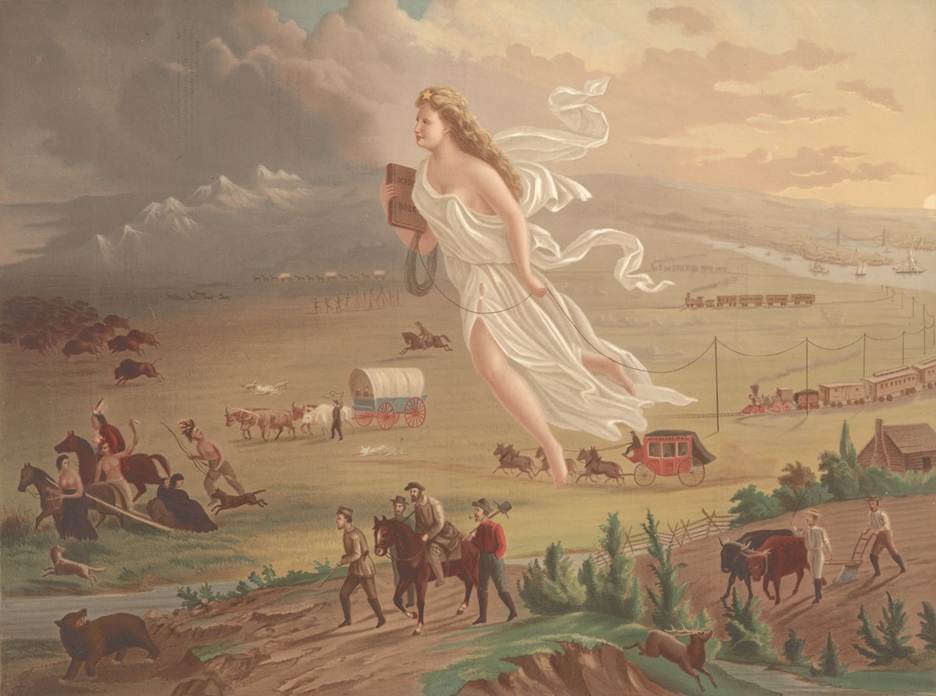

“American Progress” portrays the expansion of the United States as part of a divine plan. Civilization and American power move steadily into new lands. Those who are displaced flee helplessly toward perdition. Many in Washington still see the world that way: weaker civilizations giving way to irresistible American power.

Although “American Progress” was widely reprinted in the late 19th century, it will not be featured in any book about painterly brilliance. The artist, John Gast, was trained in lithography, not painting. He made this picture on order from a publisher who wanted an appealing image for books about the West. The result is arguably the most eloquent work of political art ever produced in the United States. It overflows with symbols and archetypes.

Dominating the picture is a robust blonde-haired angel wearing a flowing robe that evokes the glory of ancient Rome. In her hand she holds a book — a symbol of knowledge. She floats above groups of prospectors, farmers, and settlers as they trek resolutely westward. They seek to implant the American way of life in new lands.

A telegraph wire flows from the angel’s hands. Railroads steam below her. Modern technology is depicted as the engine of progress and Americans as the master of that technology.

Most poignant in “American Progress” are the Native Americans who retreat helplessly before this onslaught. The left-hand side of the picture, into which they are retreating, is dark and threatening, while a brilliant rising sun illuminates the advancing settlers. Native people and buffalo flee together. They represent the fading of races that were considered unable to adapt to American-style civilization.

In “American Progress,” the transition from pastoral Native American life to farming, ranching, and dynamic modernity is presented as peaceful. Former inhabitants of North America simply make way for the new arrivals. There is no hint of the brutality of “Indian removal” campaigns, no suggestion that Native peoples resisted, and no reference to US Army units that were, at the moment this picture was painted, violently pushing them off their ancestral lands.

The central idea behind this picture is America’s inherent virtue. It is a powerful part of our national self-image. Most Americans, like people in most other large countries, have traditionally believed that extending our influence over others brings benefits to all. Contemplating “collateral damage” muddies that picture. Nineteenth-century Americans did not want to hear about Indian massacres any more than their descendants have wanted to hear about massacres of Vietnamese, Afghans, or Gazans.

“American Progress” became popular because it portrays us as we like to think we are. The Americans in this picture come not only without malice but with limitless promise. Behind them, in the already-civilized East, are symbols of their achievement, notably the Brooklyn Bridge. Ahead lie new lands that can be likewise transformed as soon as the “merciless Indian savages,” as the Declaration of Independence put it, are gone.

Many American leaders, now as in the past, view the world as a territory to be conquered, or at least to be brought within the sphere of American influence. Those who resist are like the Native Americans and the buffalo in “American Progress” — relics of a past era that must yield to a new order.

Intriguingly, the painter who created this rosy vision of American expansion was himself an immigrant. He was born in Berlin, the son of a lithographer. If he was like most European immigrants of that period, he was inspired by stories he had heard about the New World. His painting is a tribute to what Americans had achieved and were achieving.

“American Progress” shows American expansion as benign and conflict-free. It celebrates rugged individualism and offers no sympathy for what Trump would call “losers.” That may be why the Department of Homeland Security has adopted it.

Stephen Kinzer is a senior fellow at the Watson School of International and Public Affairs at Brown University.